Ingeborg, A Viking Girl on the Blue Lagoon

Please support my film project Ingeborg, A Viking Girl on the Blue Lagoon, based on the research conducted by Dr Jacques de Mahieu, director of the Institute of Human Sciences in Buenos Aires (Instituto de Ciencia del Hombre de Buenos Aires).

According to Jacques de Mahieu (1915-1990), the Vikings went as far as the Pacific Islands. After they had helped develop a few civilizations in South America (or while they were doing so), they took their drakkars again and sailed to the Pacific. There they left traces of their presence too, in solar myths associated with white gods similar to those of the pre-Columbian peoples, in the fair skin of the aristocracy among the islanders, and in the red hat worn by tribal chiefs, as in Peru, in memory of the red or fair hair of the Vikings. Norwegian explorer Thor Heyerdahl confirmed such data but considered white migrations to Pacific islands to be even more ancient. (As explained below, Mahieu himself was aware of earlier migrations to America.)

My aim with this film is to shed light on these events by depicting the life of Vikings in the Pacific (hence the Blue Lagoon of the title). Viewers will be told the story of a young Viking girl, called Ingeborg, on the far-away islands. Let us follow her steps on the blue lagoon’s sand.

O Ingeborg, let me sing my song for you…

*

Remember that Greenland under the Vikings was a full-fledged colony replete with men, women, and children. Vikings took their women with them when they had a purpose of colonization, as the Goths had already done before them. Of course, when raids were organized for looting, they did not take women with them on such occasions.

When, after a few reconnoitering travels from Greenland and/or Vinland (their other colony on the North American continent), navigating along the coastline, they decided that those lands on the South would provide good settlements, they brought women with them.

The story of Quetzalcoatl, the blond-bearded ‘god’ of the Aztecs, tells us something about it. Quetzalcoatl was a Viking whose real name was, according to De Mahieu, Ullman*. During one of his trips further to the South, some Vikings, led by the ‘god’ Tezcatlipoca, rebelled against him. With loyal followers, he then left the rebels and the country altogether.

Whether it is these men or others from the same people who later travelled from America to the Pacific islands, I assume they took their women with them, and thus a little girl called Ingeborg might well have trodden with her soft, tender feet the warm sand of the atolls, her long sunny hair shaded by the palms of the blue lagoon, as early as 12-13th A.D.

* Ulmén: (arauc. ghulmen) m. Chile Entre los indios araucanos, hombre rico, que por serlo es respetado e influyente. (Definition of ulmén from a Spanish-American dictionary: “Among Araucanian Indians, a wealthy man, as such respected and influential.”) I don’t know if Jacques de Mahieu knew this term, which looks almost identical with the name Ullman he says was the name of the historical Viking behind the Quetzalcoatl myth. According to Aztec legends, Quetzalcoatl possessed great worldly riches. Given the likeness, here we could have the same linguistic phenomenon as reflected in such Spanish expressions as ser un Cortés (to be a Cortes) or ser un Don Juan (to be a Don Juan); that would be, proper, “to be an Ullman,” whether that Ullman is the one from Mexico or another Viking explorer and settler.

*

When the Spanish Conquistador Francisco de Orellana made his expedition on the Amazon River, he once met with the Amazons, women from an all-woman tribe. The missionary priest of the expedition, Gaspar de Carvajal, who chronicled the events, described these women as tall and white-skinned. The Indians that the Spaniards made prisoners told them these women were living on their own and that they used to get spouses from other tribes, formerly from another White tribe, now disappeared, and currently with Indians. Orellana then named the river after these women.

It should be noted that stories about women living on their own and/or training in fighting are few in history besides this chronicle. Herodotes mentions a similar tribe among the Scythians (those whom Herodotes called Scythians were later called Goths, whereas the Huns were later called Scythians, which can be confusing; if we follow classical traditions about Scythians, i.e. ancient authors such as Jornandes, Herodotes’s Scythians are the same as Goths). Likewise, Icelandic sagas deal with a few characters of so-called Virgins of the Shield, or Shieldmaidens (Skjaldmær), female warriors.

The Indians told the Spaniards that the Amazons lived in stone houses, unlike any other Indian tribe in the region. The other White people of Amazonia (those Whites who used to be in contact with the Amazons but disappeared before the period of the Conquest) were also fairly developed, with roads and stone buildings, according to the Indians**.

In academia it has long been thought, in spite of pervasive local legends about “lost cities,” that no such developed culture was possible in the region, especially since the soils would not be fertile. Two lines of argument have undermined this position. 1/ Along the river, the soil is extremely fertile; it is called terra preta (black soil) in Portuguese and is the most fertile in the world. It results from human intervention, that is, manure. 2/ Recently, American archaeologist Dr Michael Heckenberger found remnants of stone buildings in the area of terra preta, which would confirm the oral tradition about Amazons living in stone houses. From the records, no Indian tribe known today in the region has ever developed such a culture.

** Iara, senhora das águas: “Iara ou Uiara (do tupi ‘y-îara ‘senhora das águas’) ou Mãe-d’água, segundo o folclore brasileiro, é uma sereia. Não se sabe se ela é morena, loira ou ruiva, mas tem olhos verdes e costuma banhar-se nos rios, cantando uma melodia irresistível. Os homens que a vêem não conseguem resistir a seus desejos e pulam nas águas e ela então os leva para o fundo; quase nunca voltam vivos e depois os comem. Os que voltam ficam loucos e apenas uma benzedeira ou algum ritual realizado por um pajé consegue curá-los. Os índios têm tanto medo da Iara que procuram evitar os lagos ao entardecer. Iara antes de ser sereia era uma índia guerreira, a melhor de sua tribo.” (Wikipedia; my emphasis twice) This description of Amazonian Tupi goddess Iara as a green-eyed (i.e. depigmented-eyed) mermaid who previously was a member of a female-warrior tribe tallies with Orellana’s white Amazons.

Furthermore, the identification of Amazon women with goddess Iara is ascertained by the legend about the talismans known as muiraquita: “O Muiraquitã era um amuleto sagrado e mágico que as Icamiabas [my emphasis] presenteavam os homens que anualmente vinham fecunda-las. Dizem que possuem propriedades terapêuticas e grande fortuna trás a todo aquele que possuir um desses singulares amuletos. Quanto ao significado esotérico de Muiraquitã, devemos decompor seu nome em vocábulos, para compreender sua simbologia feminina: Mura = mar, água, Yara – senhora, deusa, Kitã = flor. Podemos então interpretá-lo como ‘A deusa que floriu das águas’.” Icamiabas is a native name for the Amazons; they are believed to be the ones who distributed among the tribes of the region those magic talismans whose name is said to mean “the goddess that came out of the waters,” which is precisely what is said above about Iara the green-eyed warrior goddess.

Muiraquita

*

Jacques de Mahieu’s research on pre-Columbian America went further into the past than the Vikings’ time. He writes that the American civilization of the Olmecs is a creation of white immigrants who became the ruling class over the population of Indios. The cultural achievements and the remnants of the white population of the Olmec and early Tiahuanacu culture were the base for the early Maya culture.

Later the Vikings founded a new realm at Tiahuanacu, which became the centre of civilization in America with about 100,000-150,000 inhabitants. Later they founded the Inca empire. Here the state was based on a caste-system divided between the ‘sons of the sun’ (white kings and nobles) and the aboriginal Indio population.

In Peru, the Spaniards reported several times meeting whites, especially in the upper caste of the Incas, where women were described as blonde and fair-skinned, reminding them of “Castilian beauties.” For some reason historians tend to dismiss these accounts by the Conquistadores as deceptive.

The Inquisition in America destroyed almost all documents from pre-Columbian civilizations. Jacques de Mahieu, and several others, also said that Templars sailed to America when their order was destroyed in Europe. The Templars were an order of noblemen originally founded by Norman knights. They seem to have practiced a Gnostic form of Christianity. It is said that Cathars joined their ranks after the Crusade that annihilated their community as such. Templars’ ranks being filled with Norman gentry, descendants of King Rollo and the Vikings, these men, according to De Mahieu, knew about America, as their relatives from across the Atlantic had made several trips between the two continents, informing Norman rulers of America’s existence and leaving them navigation maps. De Mahieu wrote about maps he had found in the town of Rouen, Normandy. With the help of such maps, Templars would have been able to sail to America in order to escape persecution in Europe.

When the Spaniards came, and with them the Inquisition, the Church would destroy all traces of Templar presence in America. The Gnostic teachings that the Church attempted to erase by smothering Cathars and Templars –in the same way that the Church pursued them in the Visigothic kingdom of Septimania (Languedoc), burning practically all extant texts in Gothic language– were caught in its grip as far as pre-Columbian America!

*

I have in my library an abridged version, in French translation, of the General History of the Things of New Spain (Historia general de las cosas de Nueva España, 1569) by Fray Bernardino de Sahagún, Spanish missionary in Mexico, knowledgeable in Nahuatl and all things Indian. His book was written before the prohibition by Emperor Felipe II, in 1577, imposed on all research about American Indians’ customs.

In a chapter called “Evangelization before the Conquista,” Sahagún describes various items hinting at a knowledge of the Catholic faith by Indians. He opines that the Indians had been converted to the Christian faith in a remote past but, as they were no more Christians at the time of the Conquista, they must have forgotten most of what had been carried to them by some long-dead missionaries.

Among traces of white pre-Hispanic presence in America, Sahagun names the following. Although there were no plants or cereals, such as wheat, nor animals, such as cows, of European origin in America (a fact with which Jacques de Mahieu disagrees: According to the latter, Canis ingæ, for instance, a species of dog that was living as domestic animal by some Indian peoples at the time of the Conquista, was brought there by the Vikings), there existed similar cultural elements, such as:

1/ Paintings found in Oaxaca depicting something that is very much alike the Crucifixion of Jesus Christ;

2/ Such devotional practices as oral confession and water baptism;

3/ In different places (Campuche, Potonchán), the missionaries met Indians who knew several stories from the Scriptures well.

These were, according to Sahagún, remnants of remote Christian evangelization in America. On the other hand, some customs and myths he describes remind one of Scandinavian lore. Vide, for instance, the following descriptions (my translation): “All the brave and soldiers who die on the battlefield are transported to the palace of the Sun. In the morning, at sunrise, they take on their armors and march toward the Sun with clamors and loud noise. Then they march before Him while simulating battles for their pleasure.” Which looks like the Walhalla of Scandinavian warriors (but perhaps all warriors around the world have similarly rowdy afterlife abodes). & (At the end of times or rather at the end of the present cycle) “The sun will not rise, and from outer space will come down the monstrous, horrifying Tzitzimes to devour men and women.” Which reminds one of the Ragnarok (and its monstrous dragon Nidhogg).

Finally, Sahagun describes what we already said above, that Quetzalcoatl, leader of the Toltecs of Tula (Thule?), was opposed by some of his men, here described as necromancers, chief among whom was Tezcatlipoca, god of putrefaction, and that he left his people, not without announcing that he would come back. Whence came the fact that the Spaniards at first were welcomed by the Aztecs as returning gods.

Vikigen Quetzalcoatl (The Viking Quetzalcoatl), watercolor by Ossian Elgström, 1931

(serving as cover illustration for a 1991 collection of ethnographic studies)

This work shows that the idea of Vikings having played an influential role in pre-Columbian America was already in circulation at an early date.

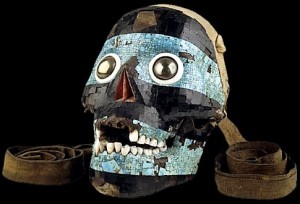

Tezcatlipoca the Necromancer

*

With regard to the Pacific islands, the following early anthropological observations about local populations by famous explorers Bougainville and Cook may corroborate Mahieu and Heyerdahl’s writings, if the former’s reports did not trigger the latter’s research in that particular direction to begin with.

“Le peuple de Taiti est composé de deux races d’hommes très différentes … [Pour les uns] Rien ne distingue leurs traits de ceux des Européens; et s’ils étaient vêtus, s’ils vivaient moins à l’air et au grand soleil, ils seraient aussi blancs que nous. … La seconde race est d’une taille médiocre, a les cheveux crépus et durs comme du crin et ses traits diffèrent peu de ceux des mulâtres.” (Voyage autour du monde) Our translation: “Taiti’s people is composed of two very different races. … [As to the first] Nothing in their traits differs from those of Europeans, and had their custom been to wear clothes rather than to live outdoors under the sun, they would be as white as we are. … The second race is of shorter size, their hair is frizzy and stiff as horsehair, and their traits are hardly different from those of mulattos.”

As to Captain Cook, here is how he describes chief Waheatua (I translate from the French version I have in my library): “He had a pretty fair complexion and his hair was smooth and light brown, reddish at the tip.” (Il avait un teint assez blanc, et les cheveux lisses d’un brun léger, rougeâtres à la pointe.)

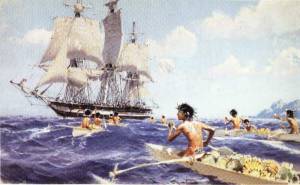

Albert Brenet, Arrivée de Bougainville à Tahiti

*

The research of Jacques de Mahieu has been carried on by Prof. Vicente Pistilli, who founded in Asuncion the Instituto Paraguayo de Ciencia del Hombre on the model of Mahieu’s Buenos Aires institute. Here is a short biography, from Pistilli’s book La Cronología de Ulrich Schmidel, Instituto Paraguayo de Ciencia del Hombre, 1980:

El autor señor don Vicente Pistili S. nació en Asunción el 27 de Febrero de 1933. Graduóse de Bachiller en Ciencias y Letras del Colegio Nacional de la Capital en el año 1951. Obtuvo los siguientes títulos universitarios : Topógrafo (1954), Licenciado en Matemática (1955), Ingeniero Civil (1958), Malariólogo y Sanitarista (1962), Licenciado en Filosofía (1965), Licenciado en Teología (1967). (…) El Profesor Ingeniero Don Vicente Pistilli S. ha colaborado con la Educación Paraguaya, siendo el primer docente a Tiempo Completo en Matemática del Colegio Nacional de la Capital. (…)

Cuando en 1972, el Profesor Doctor Don Jacques de Mahieu publicó la comunicación cientifica “Las Inscripciones Rúnicas Precolombinas del Paraguay” [my emphasis], el profesor Pistilli comprendió en toda su magnitud la importancia que tenía el descubrimiento arqueológico del notable investigador francés, quien abría una vía nueva para la investigación de nuestro pasado precolombino. Así fué como, conjuntamente con un grupo de intelectuales paraguayos, crearon el Instituto Paraguayo de Ciencia del Hombre, asociación civil de carácter científico. (…)

Pistilli ha dirigido equipos nacionales de investigacion arqueológica, con resultados positivos en todas ellas, relevándose inscripciones rúnicas, dibujos nórdicos, bosques sagrados, caminos precolombinos y monolitos tallados. Además ha realizado importantes investigaciones lingüísticas, las cuales confirman la influencia nórdica precolombina en el Paraguay.

The idea of white men’s presence in pre-Columbian America is an ancient one, as I have already hinted in my collection of short essays GNOSTIKON (français), bringing to the reader’s attention a bibliography of works in Latin, including one from Grotius. In all likelihood, among literate circles the idea was more widespread than many contemporaries may realize. Among the Puritans, there were some speculations about the Amerindians being the descendants of Israel’s lost tribes, and the Mormons’ creed expatiates on connections between the events and people of the Bible and the American continent. My first acquaintance with the subject was in Arthur de Gobineau’s book The Inequality of Human Races (1854). These ancient sources, of course, inasmuch as they do not rely on material, scientific evidence, are, on the subject at hand, speculative, even when not based on some supernatural revelation as in the case of Mormons.

Finally, we do not want to let aside some important information that may cast some doubt on several assertions we make in our essay.

Concerning, first, the conclusions of Fray Bernardino de Sahagun, Jesuit writer Blas Valera explicitly dismissed such interpretations – not naming Sahagun himself but others such as the Bishop of Chiapa (Bartolomé de Las Casas). Blas Valera is quoted by Inca Garcilaso de la Vega – who supports his point of view – in his Comentarios reales:

“A sus ídolos y dioses llaman [los indios de Méjico] en común Teutl. En particular tuvieron diversos nombres. Empero lo que Pedro Mártir y el obispo de Chiapa y otros afirman que los indios de las islas de Cuzumela, sujetos a la provincia de Yucatán, tenían por Dios la señal de la cruz, y que la adoraron; y que los de la jurisdicción de Chiapa tuvieron noticia de la Santísima Trinidad y de la Encarnación de nuestro Señor fue interpretación que aquellos autores y otros españoles imaginaron y aplicaron a estos misterios; también como aplicaron en las historias del Cozco a la Trinidad las tres estatuas del sol, que dicen que había en su templo, y las del trueno y rayo. Si el día de hoy con haber habido tanta enseñanza de sacerdotes y obispos, apenas saben si hay Espíritu Santo, cómo pudieron aquellos bárbaros en tinieblas tan oscuras tener tan clara noticia del misterio de la Encarnación y de la Trinidad. (…) Lo cual [dificuldades lingüísticas] era causa que el indio entiendese mal lo que el español le preguntaba, y el español entendiese peor lo que el indio le respondía. De manera que muchas veces entendía el uno y el otro en contra de las cosas que hablaban. Otras muchas veces entendían las cosas semejantes y no las propias; y pocas veces entendían la propias y verdaderas. En esta confusión tan grande el sacerdote o seglar que las preguntaba tomaba a su gusto y elección lo que les parecía más semejante y más allegado a lo que desea saber y lo que imaginaba que podría haber respondido el indio. Y así, interpretándolas a su imaginación y antojo, escribieron por verdades cosas que los indios no soñaron; porque de la historias verdaderas de ellos no se puede sacar misterio alguno de nuestra religión cristiana.” (I, II, cap. IV)

While the advocate of Indians Bartolomé de Las Casas had made of such findings an argument in defence of the Indians, Blas Valera imputes the findings of Christian symbols and beliefs in Amerindian cultures to linguistic misunderstanding and considers that these symbols and beliefs are just not there. He stresses that Indians are in fact too ignorant of these things even today to possibly have had a glimpse of the Christian truth in their heathen past. But Blas Valera’s argument is not quite convincing: in the light of our essay, Indians may have had in the past some encounter with the Christian faith through Christian men but only kept vague notions about it at the time of the Spanish Conquista if they had found that this religion did not suit them or had they mixed it with their own ideas and symbols. In my glossary of Americanismos and Aztequismos, I stress the similarity of the Aztec name Teutl (or Teotl) recalled by Blas Valera, with the Greek Theos, Latin Deus.

Another objection to our essay can be derived from a second passage in Inca Garcilaso’s Comentarios reales:

“El nombre de la reina, mujer del Inca Viracocha, fue Mama Runtu, quiere decir Madre huevo; llamarónla así porque esta Coya fue más blanca de color que lo son en común todas las indias; y por vía de comparación la llamaron Madre huevo, que es gala y manera de habler de aquel lenguaje; quisieron decir: Mama blanca, como el huevo. Los curiosos en lenguas holgarán de oír estas y otras semejantes prolijidades, que para ellos no lo serán. Los no curiosos me la perdonen.” (I, I, cap. XXVIII)

On the one hand, if Viracocha’s wife Mama Runtu was thus named because she was white, whereas, as stressed by Inca Garcilaso, Indian women are not, then clearly she was an exception among Indians, and reports about white Indians cannot be relied upon. On the other hand, we are dealing here with a remote past, a legend in fact, and the meaning of that legend may be that the Incas do have some white strain in their lineage, consistent with the early Conquista reports that Incas were in general whiter than their subjects.

Le fameux ouvrage du Norvégien Thor Heyerdahl à la suite de sa traversée du Pacifique en 1947 sur un radeau construit à la manière des anciens Incas (lequel radeau est exposé au Musée du Kon-Tiki d’Oslo), L’expédition du Kon-Tiki (1948), présente, outre les faits relatifs à cette traversée, la théorie de l’auteur sur le peuplement des îles de Polynésie par une race blanche venue du Pérou. Les Incas rencontrés par les Espagnols comme les Polynésiens rencontrés par Bougainville et Cook présentaient, comme nous l’expliquons, des phénotypes de race blanche : il s’agissait des restes de ces ancêtres blancs considérés par les indigènes dans un cas comme dans l’autre comme des ancêtres divins. Voici quelques extraits du livre d’Heyerdahl, dans une traduction française par Gay et De Mautort.

(i)

Presque partout, les insulaires [polynésiens] instruits savaient réciter les noms des chefs de leur île à partir du moment où elle avait été habitée pour la première fois. Et comme aide-mémoire, ils se servaient souvent d’un système compliqué de nœuds sur des cordes ramifiées, à la manière des Incas du Pérou.

(ii)

Ces nombreuses civilisations indiennes [amérindiennes] étaient à l’est les plus proches parentes de la civilisation polynésienne. À l’ouest vivaient seulement les peuplades primitives à peau noire de l’Australie et de la Mélanésie, parentes éloignées des nègres d’Afrique, et au-delà encore il y avait l’Indonésie et la côte asiatique, pour lesquelles l’âge de pierre remontait peut-être plus loin dans le temps que partout ailleurs.

Se détournant de plus en plus de l’ancien continent, objet des investigations de tant de savants, mon attention se porta vers les civilisations connues et inconnues des Indiens d’Amérique, que personne n’avait auparavant étudiées à ce point de vue [au point de vue des relations avec les cultures polynésiennes du Pacifique]. Et sur la côte le plus à l’est, où, du Pacifique jusqu’en pleine Cordillère des Andes, s’étend actuellement la République du Pérou, les traces ne manquaient pas, si l’on voulait bien les chercher. Ici un peuple inconnu avait jadis vécu et fondé une des civilisations les plus curieuses du monde, puis avait disparu, comme rayé de la surface du globe. Il laissait derrière lui de gigantesques statues de pierre aux formes humaines, qui rappelaient celles de Pitcairn, et d’énormes pyramides en escaliers, comme celles de Tahiti et de Samoa. Avec leurs haches de pierre les Incas découpaient dans les montagnes rocheuses des blocs aussi grands que des wagons, les mettaient debout ou les empilaient pour former des terrasses, des murs et des portiques monumentaux, exactement comme nous en trouvons dans les îles du Pacifique.

Les Incas régnaient sur cette région montagneuse au moment où arrivèrent au Pérou les premiers Espagnols. Ils racontèrent à ceux-ci qu’avant leur propre domination, une race de dieux blancs occupant le pays avaient érigé ces monuments colossaux, qui semblent égarés dans le paysage. Les constructeurs disparus étaient décrits comme de sages et paisibles maîtres, venus du nord à l’aube des temps. Aux ancêtres des Incas ils avaient enseigné l’architecture et l’agriculture, transmis leurs mœurs et leurs coutumes. Différents des autres Indiens, ils avaient la peau blanche et une longue barbe ; ils étaient en outre plus grands que les Incas. Finalement ils avaient quitté le Pérou d’une façon soudaine, comme ils y étaient venus ; les Incas avaient pris le pouvoir, tandis que les instructeurs blancs, partant vers l’ouest à travers l’Océanie, disparaissaient pour toujours de la côte sud-américaine.

À leur arrivée dans les îles du Pacifique, les Européens furent très étonnés de voir que beaucoup d’indigènes avaient la peau aussi blanche qu’eux et portaient une barbe. Dans de nombreuses îles, des familles entières se distinguaient d’une façon frappante par leur teint clair, leurs cheveux allant du roux au blond, leurs yeux bleu gris et des nez aquilins qui leur donnaient un aspect un peu sémitique. Les Polynésiens en général avaient la peau dorée, des cheveux d’un noir de corbeau, un nez plat et mou. Les individus roux se donnaient eux-mêmes le nom d’urukehu et disaient qu’ils descendaient directement des premiers chefs, les dieux blancs tels que Tangaroa, Kane et Tiki. Dans toute la Polynésie couraient des légendes sur de mystérieux hommes blancs, dont seraient descendus les insulaires. Quand Roggeween découvrit l’île de Pâques en 1722, il aperçut, à sa grande surprise, des blancs sur le rivage. Les habitants de cette île savaient énumérer la liste de leurs ancêtres à peau claire, depuis le temps de Tiki et de Hotu Matua, qui les premiers arrivèrent par mer « d’un pays montagneux de l’est tout desséché par le soleil ».

En poursuivant mes recherches au Pérou, je découvris dans la civilisation, la mythologie et la langue des traces surprenantes, qui me poussèrent à creuser le problème plus profondément et avec une plus grande concentration, pour arriver à identifier le lieu d’origine du dieu polynésien [Tiki].

Et j’eus enfin ce que j’avais espéré. En parcourant les légendes incas sur le roi-soleil Virakocha, qui était le chef suprême du peuple blanc disparu, je lus :

« Virakocha est un nom inca (ketchua) et par conséquent de date relativement récente. Le nom originel du dieu-soleil Virakocha, qui semble avoir été employé le plus souvent au Pérou dans les anciens temps, était Kon-Tiki ou Ila-Tiki, ce qui veut dire Tiki le Soleil ou Tiki le Feu. Kon-Tiki fut le grand-père et le roi-soleil des hommes blancs légendaires qui ont laissé d’énormes ruines au bord du lac Titicaca. Selon la tradition, les mystérieux hommes blancs porteurs de barbes furent attaqués par un chef nommé Cari, qui venait de la vallée de Coquimbo. Au cours d’une bataille dans une île du lac Titicaca, la race blanche fut massacrée, mais Kon-Tiki et ses proches compagnons purent s’échapper et plus tard gagner la côte du Pacifique, d’où finalement ils disparurent en prenant la mer dans la direction de l’ouest. »

Je ne doutai plus que le chef-dieu blanc Soleil-Tiki, qui aurait été chassé du Pérou par les ancêtres des Incas, fût identique au chef-dieu blanc Tiki, fils du Soleil, que les insulaires du Pacifique vénéraient comme le fondateur de leur race. Les détails de la vie de Soleil-Tiki au Pérou, avec les noms anciens des lieux situés autour du lac Titicaca, surgissaient de nouveau dans des légendes historiques courantes parmi les indigènes des îles de l’est.

(iii)

Les vieux Polynésiens avaient conservé le souvenir de quelques traditions curieuses, selon lesquelles leurs aïeux, arrivant par les mers, apportaient avec eux des feuilles d’une certaine plante qu’ils mâchaient pour se désaltérer et grâce à laquelle ils pouvaient, si c’était nécessaire, absorber de l’eau de mer sans en être malades. Cette plante ne poussait pas dans les îles du Pacifique, elle devait donc provenir du pays d’origine de leurs ancêtres. Les historiens polynésiens insistent tellement sur ce fait que des savants modernes ont examiné de près la question et en sont venus à la conclusion que la seule plante connue produisant un pareil effet est la coca, qui ne pousse qu’au Pérou. (…) Pendant leurs épuisantes randonnées en montagne et leurs voyages en mer, ils [les Incas] emportaient des tas de feuilles de coca, qu’ils mâchaient toute la journée pour dissiper leurs sensations de soif et de fatigue. Mâchonner ces feuilles permet par-dessus le marché de boire impunément de l’eau de mer, du moins pendant une période limitée.

(iv)

Dans les îles du Pacifique la patate ne pousse que si elle est soigneusement cultivée par l’homme, et comme elle ne supporte pas l’eau de mer, il est vain de vouloir expliquer son expansion dans ces îles éloignées les unes des autres en prétendant qu’entraînée par les courants venus du Pérou, elle a parcouru huit mille kilomètres. Cet essai d’explication d’un problème si important paraît encore plus dénué de valeur si l’on songe au fait signalé par les philologues, que dans toutes ces îles largement disséminées le nom de la patate est kumara, et que les anciens Indiens du Pérou l’appelaient ainsi. Le nom suivit la patate à travers les mers.

(v)

Dans les temps réellement anciens, ajouta le plus vieux, on les avait appelés [les radeaux] rongo-rongo, mot qui n’existe plus dans la langue actuelle, mais qu’on trouve dans les très anciennes légendes.

Le nom de Rongo transformé en Lono dans certaines îles – me parut intéressant, car c’est celui d’un des ancêtres légendaires les plus connus des Polynésiens, qu’on décrit comme ayant une peau claire et des cheveux blonds. Quand le capitaine Cook arriva pour la première fois à Hawaï, il fut reçu à bras ouverts par les insulaires, ceux-ci ayant cru qu’il était leur parent blanc Rongo qui, après une absence de plusieurs générations, était revenu du pays de leurs ancêtres dans son grand bateau à voiles. Et chez les habitants de l’île de Pâques, le mot rongo-rongo désignait les mystérieux hiéroglyphes dont les dernières « Longues-Oreilles », qui savaient écrire, perdirent le secret.